At some point Jens Witzel sees native Americans. On horses, in a long row, at the horizon, where the sky just changes from dark to light blue and the rest of the landscape is bathed in sunrise orange. Around him: dusty pale faces in a covered wagon, scraggy cattle and mules, clattering cooking utensils. Just like a Karl May novel or in one of these westerns with John Wayne or Gary Cooper, who protect the train of settlers from the natives. But the only one dragging himself through the lunar landscape of the Valley of Death is Jens Witzel.

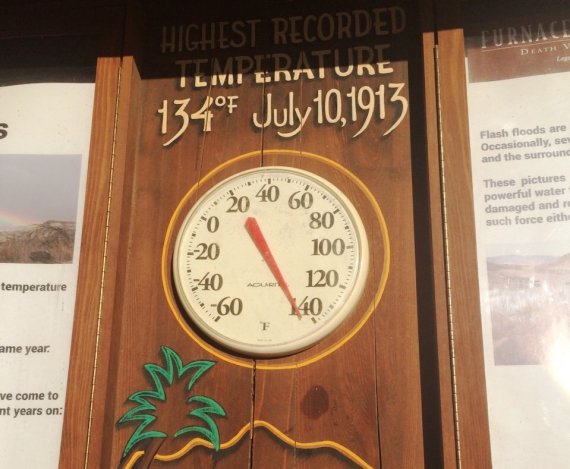

For 35 hours he's been walking through America's longest barbecue, really doesn't look very pale faced anymore and some solid hallucinations have caught up with him in the last kilometers. Because of course there are no American Indians riding on Highway 190. They only exist as a mirage in his overheated skull. There's nothing out here but heat - and a little too much of it. But that was clear from the start.

Those who take part in the Badwater 135 already admit with their registration that they are not 100% sane. The numbers: 135 miles (217 km) in less than 48 hours, from America's lowest point (85m below sea level) over three passes towards Mount Whitney, the destination is at the Whitney Portal at 2530 meters. 4450 meters up, 1859 down.

Anyone who wants to suffer this torment in 50 degrees July heat must meet tough qualification criteria: proof of three 100-mile races, one of them in the last year, experience in deserts as well as day and night races, a multi-page dossier with questions such as "What is the meaning of life? Has running changed your life? What percentage of your sports buddies describe you as good person?" Jens Witzel says: "They don't want non-swimmers with them. More like skull and crossbones rather than seahorses."

After 50 liters of liquid and 20,000 calories consumed, the reward at the finish is a T-shirt and a belt buckle - for 1200 dollars entry fee. In return, the danger of sleep deprivation, heat stroke, water poisoning, tachycardia, kidney and brain damage up to death as well as rattlesnakes and scorpions.

In 2014 the race was banned and moved to the Owens Valley - too dangerous, they said. A spokeswoman for Death Valley National Park said, "We don't want to wait for someone to die." What does your mental state need to be to want in on this? Those who have read all 75 rules and safety requirements of the organizers will be sent into the race with the following sentence: "Have fun and keep smiling! Remember, you chose to be here!"

Jens and Ricarda are here voluntarily, too, and have resolved to tackle this run through hell together - as if you don't have enough to do with yourself! Both have already finished the Badwater on their own, Jens even wrote a book about it ("Der Wüstenläufer"), and now they want to get through the ups and downs of the other together - because nobody gets trough this without crisis.

They live in Solothurn, a funny, excited couple. Ricarda, mid-50s, clerk at the canton, was competitive speed skating athlete in her youth for the GDR. At 17 she is no longer good enough for the squad. She starts a family and has nothing to do with sports for almost 20 years. Then she joins a running group for the Berlin Marathon - and is hooked by running: the longer and harder the better.

She meets Jens, who is three years younger, just behind Athens - at the Spartathlon, a 246-km run from Athens to Sparta. They get talking, in the one and a half days they cover all the topics - and become a couple. Jens, a computer scientist, also started running in his early 30s, quite harmlessly: 10 km Nikolaus run of the rowing club Herdecke. The distances become long and longer, and those who look on www.jensgehtlaufen.de where he listed his about 300 runs, get a little dizzy when reading.

When a 100-km run is no longer a challenge, he just runs 100 km plus 6000 meters of altitude difference: Ultra Trail du Mont Blanc, with a broken arm at the end. The 230 km long TorTour de Ruhr® he invented it himself. Or 1200 km through Germany in 17 days, from Rügen to the Swiss border. He even made it to the Sahara for the Marathon de Sables: 250 km in six stages, lugging luggage and food himself. Doesn't sound any less exhausting than the Badwater Run, does it? "Pah," Jens says and waves off, "Badwater is a completely different category. The Sahara run, on the other hand, is a scout trip. Badwater is beyond the notion of normal walking. 50 degrees: It's like someone holding an infrared sun or a hair dryer in your face, a feeling like the hot flush of air hitting your face when you open the oven to get out the rolls - and that for two days non-stop. Run over 200 km in this heat: That's very special." No contradiction, nowhere.

The two of them aren't the only crazies among the 100 starters. There's Ed Ettinghaus, a charity runner who wears a polyester dunce cap during the heat madness. Or Danny Westergaard from L.A., who once arrived at the finish line, climbed the summit of Mount Whitney (4421m), ran back to the start - and repeated the whole thing twice, a total of 6 x 217 km. Why? Westergaard said, "My father had just died, and I wasn't finished thinking at the finish."

In addition: a team in pink Tutus, an bunch of Austrians in traditional costume with gamsbart, one with war paint, one with a paralyzed face half after a stroke, and one who had all toenails removed so as not to get blisters. At his first Badwater, Jens thought: "Who could have smuggled in all these mutants? What kind of freak show did I end up in?" Today he greets his colleagues with a handshake.

Then there's the crew of three: "People who have traveled halfway around the world just to pour ice over my head," says Jens. Without the helpers in the accompanying car, who take over the basic supply after every mile, nobody would see the goal. "Crew is more exhausting than running because you always have to be rational despite the heat and insomnia. The runner can turn off, almost like he's on drugs."

And because you forget the names of your friends in the eternal heat, many T-shirts have first names on them. "You have to give control to the crew," explains Jens, "they have to make sure you eat enough, drink enough, be covered with ice." He is not wearing functional clothing, but a long-sleeved shirt and long trousers made of cotton - because the icy water spray lasts longer. After a mile, everything is as dry as it was in the tumble dryer. The ice cubes in the drinking bottles have turned into warm water after two stops. "If you put it on the roof of the car for another ten minutes, you can use it to mix mashed potatoes," jokes Jens.

In fact, the menu includes mashed potatoes, noodles, potatoes, white bread, non-alcoholic beer, cola ("sugar, calories and caffeine: all great") and iced coffee ("nothing but milk with sugar"). No electrolytes, isotonic drinks, gels, powders: "It foams up the stomach in the heat and goes up like in a washing machine," says Jens, "the stomach switches to playback mode: everything has to go out. »

In the extreme temperatures, the feeling for speed and time is also lost. Jens approached his first Badwater in a controlled manner, but then he did what you are not allowed to do: Let's fly! No sprint, but not at the right pace for the event. "At mile 60, I threw up everything I had, three, four, five times, until there was nothing left. The stomach is the indicator of whether it's working or not. It's much harder to train than the legs because you can't feel the situation at home. It cannot process more than one liter of liquid per hour. If you spill more on it, you'll only get a Biafra belly."

The only question now is how to run in this heat. Once 56 degrees centigrade were measured. And at night it is still 45 degrees, because the heat, which has risen during the day, comes back at night as a hot fall wind into the valley. Humidity: less than ten percent. Sweat: evaporates when leaving the pores. The plan of Jens and Ricarda: do not fight against the heat, but accept it! Win the battle in your head.

Five days before the start for preheating to Las Vegas, where it is already 40 degrees. All air conditioners off, the body get used to insanity, yet you can hardly move the first few days. Ricarda was at the end before her first Badwater: "You think: 'It's not possible. You can't walk tomorrow.' But you're still running. You arrive somehow, but the next day you think again: 'That's not possible. How did I do that?"

Jens describes the scenario as follows: "Hot wind like from the engine of a fighter jet, mouth completely dry, mucous membranes cracked. You can feel how the warmth penetrates the body, taking possession of it like an invisible alien power, like in a field test for microwave weapons. I feel like a dry riverbed, like a bone-dry tinder sponge - a spark of fire, and I run to the finish as a torch. The sun is already burning hot in the morning as if my calves were lying on the grill. Now I know how hot hell on earth can get."

In order not to get stuck on the asphalt as human sweats, Jens has made friends with the shoulder, he calls it Forrest, after the endless runner in "Forrest Gump". On the white stripe, the reflective heat of the asphalt is a bit less - reason enough to fraternize with the eternal companion. Forrest forever.

Apart from Forrest there is little to see: no meadows, no trees, only salt crusts, desert and a flickering horizon.

Whereby Jens says: "When you have finished all thought programs after the first hours, you can no longer think at all. Your head's empty, no more brain block. You don't have to think rationally anymore, you can see what's happening all around. You have time to observe things without judging them. You don't have the strength to put them in a drawer anymore. A very pleasant condition. Someday you'll be beyond time. You know the clock's ticking, but you can't go any faster. You feel like everything's passing you by. But at some point, you don't care. It's very grounding, a form of humility. You can still have such a big mouth, so much training, so many sponsors on your back: "It's the same for everyone: everyone pukes, everyone hikes, everyone suffers."

Jens doesn't consider giving up for a second. "I hate to argue with myself during a run. I'm so frustrated, tired and broken on the way - if you start with questions of meaning, it won't get you ahead. You're in this race, so finish it too! There's just, I want this, or I don't want this. Someday you're gonna have to pinch your backside. This has nothing to do with logic either."

Rather the feeling of being at home in this desert creeps up on him, whereupon he asks himself: "What kind of strange person am I?

Well, someone who sees American Indians where there aren't any. But that's only because Ricarda galloped away. Usually they always ran together, had their highs and lows exactly opposite, which cost time, but no matter. Ricarda had just been in a bad low, had been whining for six hours, wanted to lie down to sleep when the sunrise and a slight gradient brought her back to life. "Run ahead," says Jens and sees her accelerate past other runners, one of whom calls out to her: "Young lady, you will pay for this!

She tames her overconfidence, knows long before the finish that they will succeed. In contrast to other ultra runs, the Badwater doesn't go over hill and dale, but up another 1500 metres of altitude over the last 19 kilometers - too steep for a race if you have 200 km in your legs. So all runners hike: the longest showdown in the world. The home straight adrenaline can be enjoyed for three or four hours. Jens and Ricarda celebrate the last kilometers: "The closer you get to your destination", Ricarda says, "the slower you get, because you know: it'll be over soon".

After 217 kilometers in the Valley of Death, the finish line is unspectacular: When a runner comes, a belt is briefly held across the road, the finisher shirt and belt buckle are handed over, photos are taken in front of the sponsor wall, and then the road is clear again - and the runner stands there with his emotions.

Jens describes his feeling after 39 hours and 19 minutes as follows: "At the finish it's not as emotional and euphoric as you might imagine. Of course one is glad not to have to move anymore, but there is no feeling of happiness, no emotional hype, rather emptiness and sadness. The preparation and the race itself were so extensive and long that you don't realize at the moment that it's over. Basically, it's not a race about arriving, but about the moment when the uncertainty of whether you can do it tips over into certainty. Now I can understand when someone says: 'It is not over yet. I have to turn around and walk back. I'm not done yet!'"

Sports BusinessSki Mountaineering Goes Olympic: What Milano-Cortina 2026 Means

Sports BusinessSki Mountaineering Goes Olympic: What Milano-Cortina 2026 Means

- ISPO awards

- Mountain sports

- Bike

- Design

- Retail

- Fitness

- Health

- ISPO Job Market

- ISPO Munich

- ISPO Shanghai

- Running

- Brands

- Sustainability

- Olympia

- OutDoor

- Promotion

- Sports Business

- ISPO Textrends

- Triathlon

- Water sports

- Winter sports

- eSports

- SportsTech

- OutDoor by ISPO

- Heroes

- Transformation

- Sport Fashion

- Urban Culture

- Challenges of a CEO

- Trade fairs

- Sports

- Find the Balance

- Product reviews

- Newsletter Exclusive Area

- Magazine