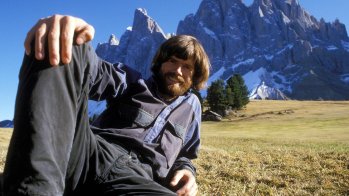

Reinhold Messner’s greatest performance was having survived the 14 eight-thousanders and unsuccessful attempts in between. When you push yourself to your limits like today’s world-class mountain climbers, it’s an art of measuring it out accordingly and knowing when to stop. That’s because extreme mountain climbing can be addictive, of that there’s no doubt.

“Ueli Steck didn’t Care about Getting Famous”

Nevertheless, the true greats of the craft don’t do it for the publicity. Ueli Steck was not as dependent on his sponsors as other mountaineers, and in this respect hardly felt any pressure. His motivation was very simple: When you accomplish peak performances, you want to ramp them up.

When you notice that you’re fit, you always want more. That was Ueli’s drive. Not getting renowned and famous. He didn’t care about that. He was always a very modest and down-to-earth person. Just incredibly talented and especially hardworking.

Read here: The Tragic Death of Ueli Steck on the Nuptse Mountain

In the combination of speed and demanding terrain, Ueli was the best mountain climber in the world. The technical challenge in traversing Everest and Lhotse wasn’t the crux – he definitely had demanding mountain terrain down pat. The north face of Eiger, for instance, is much more difficult from a technical perspective.

The difficulty would have been the long period above 8,000 meters, the bivouac in the death zone on the Everest south saddle. But he had that down, too. What he had planned was not hubris.

It’s problematic when laypeople pass judgement on peak performances in mountain sports. That’s when the criticism comes in: It’s suicidal, it can’t be answered for anymore. No mountain climber will make this reproach of Ueli, but someone who doesn’t understand the enthusiasm and passion for what he did would.

The laypeople also don’t have any idea that someone like Ueli always has to meticulously plan for his tours, that he trained like a man possessed. He planned everything, he optimized every factor he could influence. And of course he knew that he could still lose his life.

40 Years After Messner's Wild Solo Ride: The World's Best Climbers

“If a Crampon Slips, then that Was it”

You very simply have to determine: World-class mountaineering moves in a place where there’s always a residual risk – and not a small one by far. Especially in extreme mountain climbing. And it’s also clear: The more often someone puts themselves in danger, the greater the probability that something will happen someday.

Ueli Steck Loses His Life in an Accident in the Himalayas: The Reactions from the Outdoor World.

The fall actually happened on an acclimation tour on the Nuptse. I once met Ueli at ISPO MUNICH; he described to me that he saw the major danger in 50-degree-steep ice, because he didn’t use his ice equipment at all there in order to be even faster. He just stood on the front points of his crampons.

And if a crampon slips, then that was it. I assume that precisely that is what happened on Nuptse. Tragically, it’s often the purportedly easy terrain that becomes the doom of peak mountain climbers. One Herrmann Buhl, for instance, lost his life on a cornice on the Chogalisa in Pakistan, not in extreme terrain.

It’s a sober assessment: The death rate of the top people is high. After my accident solo-climbing in the Black Forest, which I was very lucky to survive, I quit doing solo ascents. I’ve become more risk-averse and converted to the scaredy-cat faction. Ueli, on the other hand, was at an age where the achievement potential was still there. He still wasn’t ready to power down those kind of aspirations. Traversing Lhotse and Everest would have been his culmination.

“We Just Raised our Hats: Madness”

For me, Ueli leaves behind a unique legacy. For me, he was very clearly co-responsible for the fact that mountain climbing, which before had stagnated for decades, gained another explosion in achievements. He dominated the combination of hard and fast, confident and elegant at the same time.

The legendary Colton-MacIntyre route on the Grandes Jorasses that took me 14 hours, in my mid-fifties with a young, strong partner, Ueli managed in three hours. We just raised our hats: Madness! He didn’t even know the route. He absolutely earned his nickname “The Swiss Machine.”

The Author:

In 1978 Bernd Kullmann stood on Mount Everest's summit wearing Levi's jeans. The story of this unusual ascension is world famous in the climbing scene. "Mr. Deuter" is still a big player in the outdoor sector, even though the 62-year-old isn't CEO of the rucksack producer anymore.

OutDoor by ISPOOutDoor in transition

OutDoor by ISPOOutDoor in transition

- ISPO awards

- Mountain sports

- Bike

- Design

- Retail

- Fitness

- Health

- ISPO Job Market

- ISPO Munich

- ISPO Shanghai

- Running

- Brands

- Sustainability

- Olympia

- OutDoor

- Promotion

- Sports Business

- ISPO Textrends

- Triathlon

- Water sports

- Winter sports

- eSports

- SportsTech

- OutDoor by ISPO

- Heroes

- Transformation

- Sport Fashion

- Urban Culture

- Challenges of a CEO

- Trade fairs

- Sports

- Find the Balance

- Product reviews

- Newsletter Exclusive Area

- Magazine

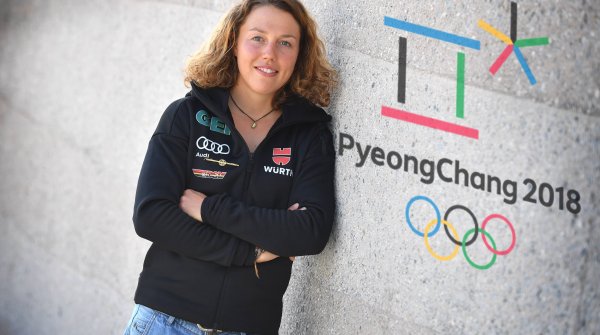

![mb-170504-kaltenbrunner By ascending the K2 in 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner was the first woman ever to ascend all eight-thousanders and the first who managed this without additional oxygen. However, the 1970 born Austrian is not keen on records. " If it was all about records, I would have taken the easiest route everywhere [...] Being the first is not important to me".](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_image_article_phone_1x/public/b/79/70/79706302-imageData.jpg?h=8fe3b20d&itok=abz5O8dZ)

![mb-170504-kaltenbrunner By ascending the K2 in 2011, Gerlinde Kaltenbrunner was the first woman ever to ascend all eight-thousanders and the first who managed this without additional oxygen. However, the 1970 born Austrian is not keen on records. " If it was all about records, I would have taken the easiest route everywhere [...] Being the first is not important to me".](/sites/default/files/styles/gallery_thumbnail_article_phone_1x/public/b/79/70/79706302-imageData.jpg?h=8fe3b20d&itok=9-Ka4q08)